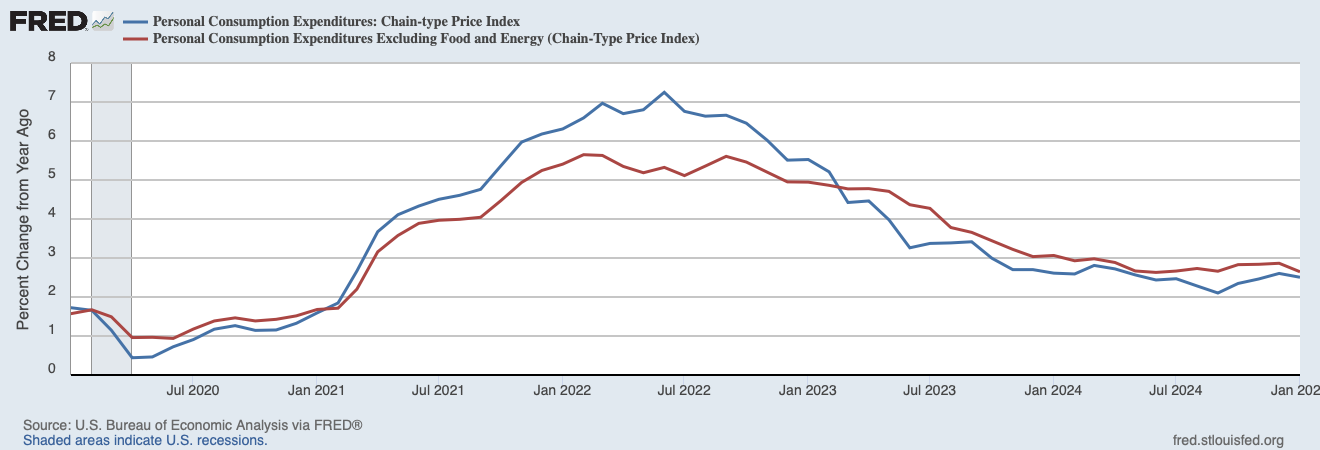

Federal Reserve officials have warned that the disinflation process would be uneven. The latest data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) confirms as much. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI), which is the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, grew at an annualized rate of 4.0 percent in January 2025, up from 3.6 percent in the prior month. PCEPI inflation has averaged 2.6 percent over the last six months and 2.5 percent over the last twelve months.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, also picked up. Core PCEPI grew at an annualized rate of 3.5 percent in January 2025, up from 2.5 percent in the prior month. PCEPI inflation has averaged 2.6 percent over the last six months and 2.6 percent over the last twelve months.

Figure 1. Headline and Core PCEPI Inflation, January 2019 – January 2024

The recent uptick in inflation should be evaluated in context. Many prices update each January, which marks the start of a new year. The BEA attempts to account for this by making seasonal adjustments—that is, smoothing the time series by reporting a bit less than measured inflation in January (when actual price increases tend to be larger) and a bit more inflation in other months (when actual price increases tend to be smaller).

A simple example helps illustrate how seasonal adjustments work. Suppose all prices adjust once per year, in January. Suppose further that prices increase 2.0 percent each January and 0.0 percent every other month. Seasonally adjusting the corresponding price level series would result in a monthly inflation rate of nearly 0.2 percent—or, 2.0 percent annualized—even though the actual inflation rate in eleven of the twelve months is 0.0. Rather than jumping up 2 percent each January, the seasonally-adjusted price level would grow steadily across the year, with prices this year always 2 percent higher than they were twelve months earlier.

Similarly, a simple extension helps illustrate when seasonal adjustments do not work so well. Suppose, once again, that prices adjust once per year and that, in normal times, inflation averages 2 percent per year. Next, consider what the seasonally-adjusted series would look like in an abnormal year, when inflation is actually 6 percent. The seasonal adjustment moves roughly eleven twelfths of the usual 2 percent inflation from January to the other months, even though no actual price changes occur then. But it does not move any of the unusual inflation—the additional 4 percentage points in January.

Of course, reality is much more complicated than these simple examples. Some prices adjust many times per year, whereas others adjust just once or twice. And the trend rate of inflation is not known. It must be estimated based on the historical data. Still, at risk of oversimplifying, the BEA essentially accounts for the average price change for a typical month in light of the average price change for a typical year. This works well in normal times, when prices are growing more-or-less as usual. It does not work so well when prices are persistently growing faster than average, as has been the case over the last few years.

Since the price increases across the year have been larger than usual over the last few years, the seasonal adjustments have generally removed too little in high-inflation months like January and added too little in the low-inflation months. The resulting seasonally-adjusted series is both more volatile than usual, though still less volatile than an unadjusted series would be. A better seasonal adjustment would spread some of the big January 2025 increase over the prior six months and subsequent six months, further reducing the volatility of the seasonally-adjusted series. Alas, we do not have a better seasonal adjustment. Instead, we must evaluate the data in light of the additional volatility.

One way to look through the less-than-ideal seasonal adjustment is to look exclusively at the January data. Inflation averaged 6.1 percent in January 2022. It averaged 6.3 percent in January 2023; 5.2 percent in January 2024; and 4.0 percent in January 2025.

Another way is to look at twelve-month inflation rates. Over the twelve-month period ending in January 2022, the PCEPI grew 6.3 percent. It grew 5.5 percent over the twelve-month period ending January 2023; 2.6 percent over the twelve-month period ending January 2024; and 2.5 percent over the last twelve months.

Both approaches indicate inflation has fallen. Moreover, imperfect seasonal adjustments means the underlying—or, average—rate of inflation is probably less than the rate recorded in January. So long as twelve-month rates continue to fall, we should not be concerned about an inflation resurgence.