One of the big problems in the American housing market today is the dearth of “starter” homes. These are smaller, affordably priced homes available for sale and ownership, often appealing to young families as their first home ownership opportunity. According to Zillow data, the number of US cities where a starter home (defined as being in the lower third of home values in a region) costs at least $1 million tripled between 2019 and 2024. A typical house in the lower third of the market now costs over $1 million in more than 200 cities.

Redfin finds that the income needed to afford a median-priced starter home in the United States fell slightly in 2024 as mortgage rates dropped, even though prices kept growing. But the income needed to buy a starter home is still nearly double what it was in 2019 and more than three times what it was in 2012.

The Vanishing Starter Home: Why Young Buyers Are Struggling

When young people face difficulty in buying their first home, it creates problems: fewer young people are marrying and having kids, possibly because they don’t want to raise them in an apartment. And young people who feel shut out are losing faith in (what they perceive as) a free market system.

Why are starter homes so hard to find in much of the nation? Zoning regulations require a large amount of land for each house, known as minimum lot sizes. (Some more abstruse regulations like “floor area ratios,” “minimum frontages,” and the like have similar effects.) Requiring more land per house makes it harder to subdivide land. For example, if you have a 50-acre lot and the town requires a minimum lot size of five acres, you can only build, at most, 10 homes on that lot. If the minimum lot size were one acre, you could build 50 homes.

The cost per home will be far lower for one of 50 lots rather than one of 10, not just because of the cost of the land that runs with each house, but because of economies of scale. When developers build a few dozen homes at once, they can take advantage of volume discounts and a consistent team of workers who stay on site until the job is done. As Harvard economist Ed Glaeser once noted, “If you want people to have affordable clothing, you don’t tell them to get a custom suit on Savile Row. In the same way, it’s impossible to have affordable housing if you force every home to be a custom build.”

Lot Size Minimums Drive Up Housing Costs

Minimum lot sizes increase housing costs. A study of eastern Massachusetts found zoning districts that increased minimum lot sizes saw housing prices increase by about 40 percent after 12 years, compared to similar homes in districts with unchanged minimum lot sizes. Another recent study found that minimum lot sizes reduce housing development and redevelopment of existing neighborhoods. This unpublished study of localities nationwide from a couple of prestigious economists finds that, comparing neighboring communities with and without stringent minimum lot sizes, housing prices are $30,000 higher in the more stringent community and house sizes are larger. Predictably, the density of housing is lower. A recent study of Texas (PDF) found that home-building is concentrated at just above the minimum lot size, implying that these regulations are often binding on developers.

These studies aren’t cherry-picked. I found no post-1999 studies that contradicted these findings. Minimum lot sizes don’t always bind, but when they do, they reduce the supply of housing and raise the cost, often significantly.

Current Homeowners Don’t Want Density

Why do municipalities adopt strict minimum lot sizes? One reason is simply that many homeowners prefer low density. Ideally for the homebuyer, you buy a house affordably when minimum lot sizes are low or nonbinding, and then vote to support tighter zoning restrictions that raise your property value by prohibiting the building of more homes nearby.

There are sometimes legitimate public health and environmental reasons for minimum lot sizes. If everyone is digging wells, it’s reasonable to limit residential density to ensure there’s enough groundwater for everyone. Septic systems also require enough land to disperse the leachate safely.

But in most of the Northeast, typical suburban minimum lot sizes are far above those justified by public health or environmental considerations. In New Hampshire, the state Department of Environmental Services certifies wells and septic systems and in doing so enforces lot size requirements based on slopes and soils. Additional municipal standards are not necessary, yet most towns enforce them. Under 15 percent of the buildable land area in the state is available for single-family development on lots of less than an acre, according to the New Hampshire Zoning Atlas. Some cities, like Hartford, Connecticut, allow small-lot single-family on a lot more land, but some, like Flagstaff, Arizona, allow it on very little land.

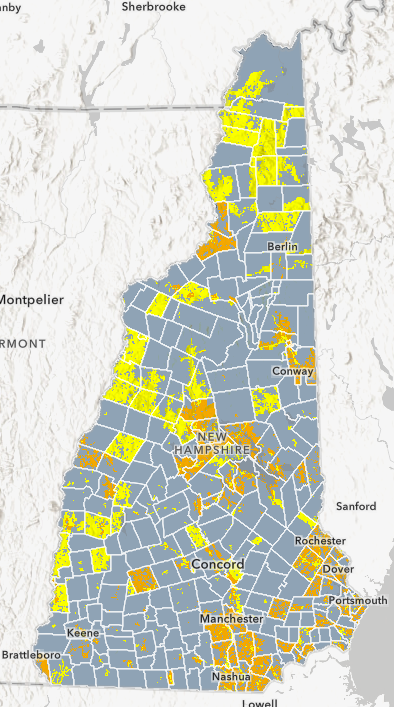

Figure 1 shows where single-family housing is allowed on lots of less than two acres. The orange areas are zoned residential-only, while the yellow areas allow commercial uses too, and the gray areas are either closed for single-family development, unbuildable, or available for single-family development on lots of two or more acres. Much less than half of the land area of the state is available for single-family development on lots of less than two acres. It tends to be central cities, older inner-ring suburbs, and extremely rural areas in the North Country and along the Appalachian spine that allow it.

Advocates of large minimum lot sizes claim that they “preserve rural character.” But large minimum lot sizes promote exurban sprawl by forcing new housing units to be developed farther apart. They therefore undermine the goals of wilderness and farmland preservation. Even a five-acre minimum won’t preserve farms, which have to be on a much larger scale. Napa County, California has perhaps the highest minimum lot sizes in the country, at 100 acres. At that scale, minimum lot sizes have the potential to protect farms, but only at the cost of essentially banning residential development and hurting farmers who lose the value of the development option. For these reasons, the American Farmland Trust supports limiting minimum lot sizes, which promote “low-density residential developments” that “fragment the agricultural base and limit production.”

Municipalities Refuse Action on Affordability

New Hampshire has two pending bills to remedy this problem by limiting minimum lot size requirements. I submitted written testimony to the Senate Commerce Committee on SB84, which would limit minimum lot sizes “on a majority of land zoned for single-family residential uses” to half an acre where sewer service is available, one acre where water is available but sewer is not, and an acre and a half where neither water nor sewer is available. A similar bill, HB459, requires soil-based lot sizing consistent with state standards where utilities aren’t available.

If one of these bills passes in more or less its current form, it would go a long way toward freeing up the market for starter homes in New Hampshire. It would also preserve a diversity of neighborhoods for people who really want to pay a lot of money to live in large-lot neighborhoods, because towns could still impose unlimited minimum lot sizes on some of their residential land.

The New Hampshire Municipal Association is pushing back hard against these bills, as local government associations have done in other states, so far successfully. No state has yet enacted into law a statewide limit on minimum lot sizes, though Vermont successfully limited minimum lot sizes in places with existing water and sewer infrastructure.

Without state action, the starter home problem will just get more severe. Municipalities need guardrails on their zoning powers, both to safeguard private property rights and allow the free market to address the housing crunch.