Today (Mar 19, 2025) is Match Day — the medical equivalent of the NFL Draft — when would-be medical residents are matched with sponsoring clinical programs.

For thousands of America’s brightest young people — 3,350 graduates in 2024 — today will be among the worst days of their lives. Those thousands of medical students go unmatched, which means they’re shut out of the only path to legally practice medicine in the United States. No residency? No license. For an unmatched graduate, a med school degree won’t mean a thing.

Demand for doctors continues to rise, but the supply has not been allowed to keep up. Fewer than half of med school applicants find a spot in the nation’s 154 medical schools, and up to 10 percent of graduates won’t get a residency (though a few more may be placed through the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program — SOAP). Hospitals are desperate for staff, small towns are begging for family doctors; yet, perfectly qualified doctors-in-waiting are locked out of the system.

Who’s administering this near monopoly? What created this massive bottleneck of healing potential, which is expected to result in a shortage of at least 86,000 physicians by 2036?

The answers, unsurprisingly, are the federal government and Congress, thanks to a 1997 spending bill supported by a cartel of campaign donors.

A Bureaucratic Bottleneck on Medicine

Ninety-eight percent of all US medical residencies are funded by the federal government: 86 percent through Medicare and Medicaid and Veterans Affairs. Another 12 percent comes from state matching of federal Medicaid funds (funds confiscated from the people of those states, in the first place). Provisions set by Congress decide how many doctors can be trained annually, and effectively bars all others from practicing, even if they are highly qualified. You can’t independently practice medicine in the United States without having first been matched with, and then completed, a three-to-seven year residency.

Most readers are likely aware of the looming physician shortage: current projections estimate that within the next decade, the US could face a shortfall of up to 120,000 doctors, posing a significant challenge to an aging population’s healthcare needs. The doctors we do have are often misallocated both in terms of specialty (we lack OB-GYNs and family physicians, but have an overabundance of specialists), and geography. The problem isn’t a lack of aspiring doctors — it’s an artificial training shortage imposed by Washington.

Like so many of our most daunting policy problems, the doctor shortage stems from a past federal attempt to fix a smaller issue.

Back in the 1980s, medical literature and discussions with policymakers were dominated by the threat of a doctor surplus. “Cuts in Schooling Urged to Prevent Doctor Surplus,” wrote The Washington Post in 1980; “Predicted Doctor Surplus Brings Plea for Caution,” reported The New York Times. Both were referencing “GMENAC,” a federal committee study (PDF) presented to The Department of Health and Human Services the same year. The panel of experts called for a 17-percent cut in medical school enrollment to head off a predicted glut of some 70,000 physicians, including 10,450 “too many” OB-GYNS.

The worry then was that too many doctors would create a surge in demand for care — physician-induced demand, the reports to Congress warned. So the prevailing wisdom of the time was to address rising health care costs by reducing the number of doctors.

Congress, in its infinite wisdom, decided to cap the number of residency slots funded by Medicare. Congress’s residency cap sidelines up to 10 percent of potential doctors (the ones who’ve already graduated medical school) while patients wait weeks or months for appointments.

The Role of Residency

Medical resident training is the only pathway to becoming a licensed physician. However, access to these training programs is tightly controlled, with Congress holding the monopoly and federal agencies overseeing the process.

In the early 1970s, federally appointed review committees had eliminated any path to becoming a general practitioner (apprenticeship and service abroad, for example) that didn’t include a mandatory, federally funded three-year medical residency.

The 1997 Balanced Budget Act, responding to fears of rising costs due to a physician surplus, capped residency training funds at their 1997 level, where they remained for 25 years. A hospital already training 20 residents could keep its 20 residency slots, but the government would not allow it to hire or train more doctors. Nor could new donors or hospitals create new residency training programs. The total number of medical residents — 98,258 in 1997 — was virtually locked in. The government even shuttered medical schools (despite ample numbers of qualified applicants) and paid some hospitals not to train doctors.

Since then, the US population has grown by over 75 million people, and shifted demographically and geographically, while the number and location of doctor residency positions barely budged. The population aged, medical technology improved, and lives lengthened. But the training of doctors had been cryogenically frozen the year Titanic and Men in Black debuted.

That was 28 years ago. Today’s unmatched residents weren’t even born yet when their opportunity to serve was artificially excised.

The Economics of a Manufactured Shortage

The misallocation of medical graduate training isn’t just a healthcare problem—it carries a heavy economic price. The physician shortage costs the US billions annually in lost productivity and higher healthcare costs. A recent report found that adding just 275 medical residency slots in Arkansas over six years could generate $465 million in economic activity. Now imagine scaling that across all 50 states.

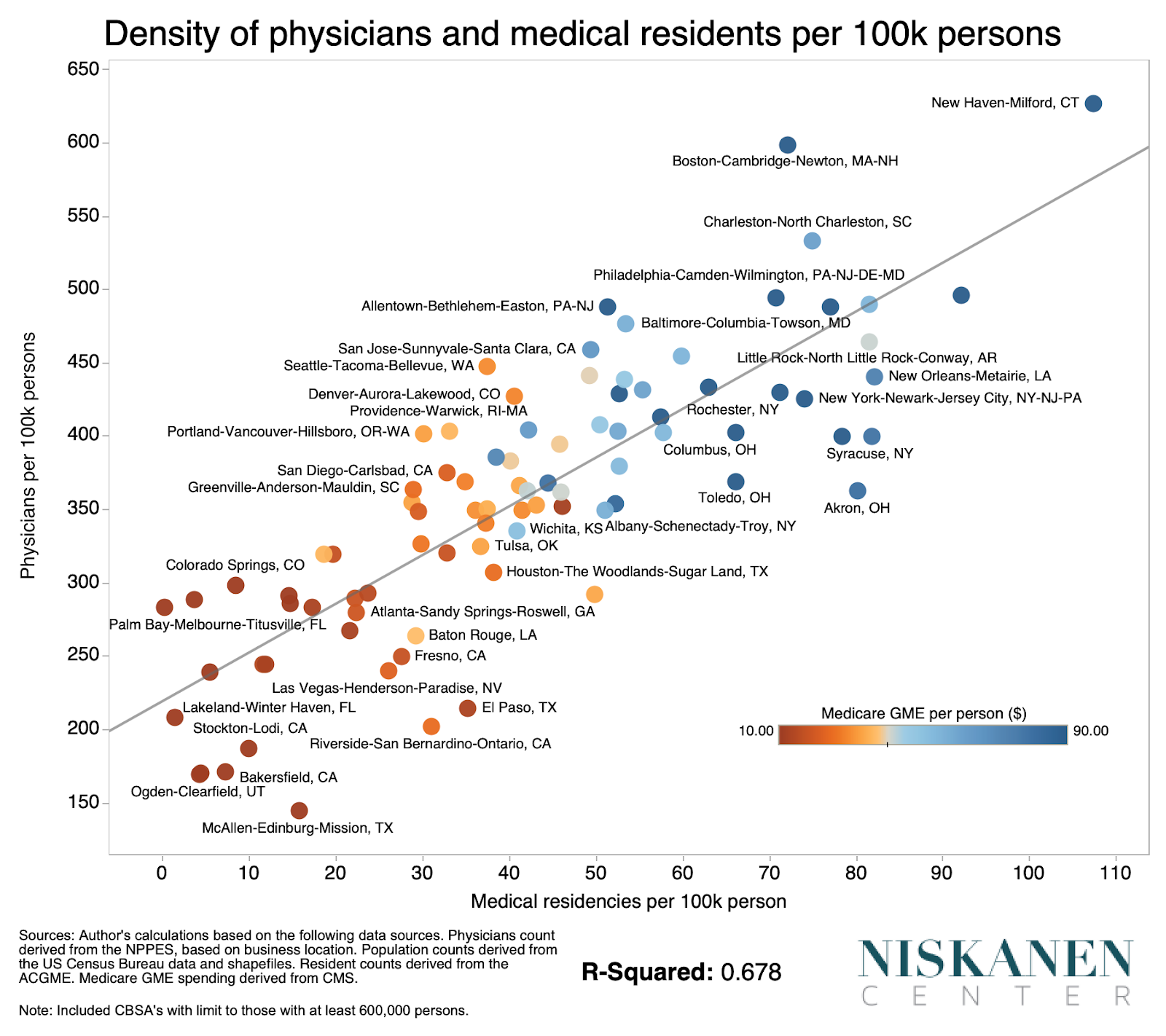

The problem isn’t that we don’t spend enough on training doctors, but that the funding is so poorly distributed that it creates systemic distortions in the availability of medical care. Federal dollars spent on medical education don’t go to students; the funded spots are owned by institutions, mostly teaching hospitals. Because those institutions are generally in high-concentration urban areas (or at least the urban areas that were highly concentrated in 1997) and because general practitioners tend to open practices within 100 miles of where they completed a residency, new doctors for rural America are disturbingly difficult to come by.

Congress has taken baby steps, adding 1,000 new Medicare-supported residency slots in 2021, in the $2.3 trillion Consolidated Appropriations Act. That’s a start, but it’s a rounding error compared to what’s needed. The federal government also designated some “medically underserved areas” and annually routes some new graduates to those areas.

J.D. and Turk from Scrubs, Mark Green and Doug Ross from ER, and the titular Meredith Grey of Grey’s Anatomy are perhaps our most culturally familiar examples of these aspiring young doctors. But we rarely consider that their medical studies are not funded by hospitals, surgical practices, nor with any connection to services provided to patients.

Congress insisted, at the behest of the American Medical Association, that only the federal government could train and license doctors. Then it refused to do so. In attempting to avert overspending on a doctor surplus, it induced a doctor shortage. The United States now has 50 percent fewer practicing physicians per capita than Sweden or Germany and spends roughly 50 percent more per capita on medical care. Unsurprisingly, US doctors also earn much higher salaries.

Many advocates and a handful of bills in Congress call for increasing the number of resident slots or uncapping residency funding. Allowing hospitals to create more training spots would help alleviate the shortage. But that only treats the symptom of this government monopoly.

While some licensing structure (preferably at the state level) must continue to exist, eliminating per-institution caps on resident training, and expanding the pathways by which one can become a practicing physician — restoring apprenticeship, for example — could go much further to reduce the stranglehold of a few doctors over the future of American health care.

The current residency cap isn’t just bad policy. It’s malpractice.