In a recent blog post, Matt Yglesias chides northeastern Republicans for opposing pro-housing deregulation in state legislatures:

Republicans have led several major pushes for housing reform in red states. These efforts are inevitably GOP-led because these states have GOP-controlled legislatures, and to the best of my knowledge, none of them have met with uniform GOP opposition. But in New York and Maryland, we’ve seen divided Democrats unable to push through housing reforms supported by Democratic governors in the face of relentless GOP hostility.

He also references a recent bill that passed in Connecticut with exclusively Democratic support, Republican politicians in Virginia and New Jersey who have made statements against any attempts to legalize more home-building, and even a free-market Maine think-tank that opposes any diminution of local zoning powers.

So what’s the explanation? Yglesias’ own view is that “a perennial favorite activity of GOP-controlled state legislatures in places like Tennessee, Texas, and Georgia is passing laws to preempt local efforts to raise the minimum wage or otherwise lib out” (presumably referring to city-level gun control, tenant protections, and the like, as well as school policies on books, LGBT issues, and the like).

Because they’re used to preempting cities on other issues, preempting local zoning feels like a natural move for red-state Republican legislators, especially when they can focus it on larger cities and exempt suburbs and small towns, as recent legislation in Texas and Montana has done.

But “blue-state Republicans are anti-housing” doesn’t explain California, where Republicans from rural and inland areas joined just over half of Democrats in the state Senate to pass SB 79, requiring upzoning near transit stops. Of course, many Republicans in California are anti-housing – conservative Huntington Beach has even flirted with imposing strict rent control to stop apartment construction – but some of them are not.

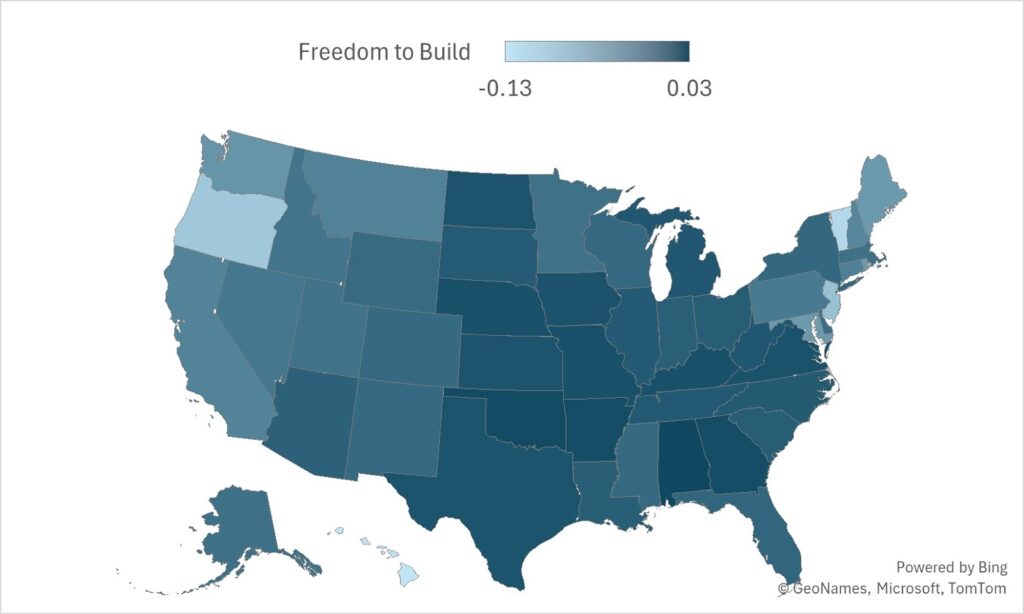

Note: Constructed from Ruger and Sorens (2023), including only policies related to regulations on building housing.

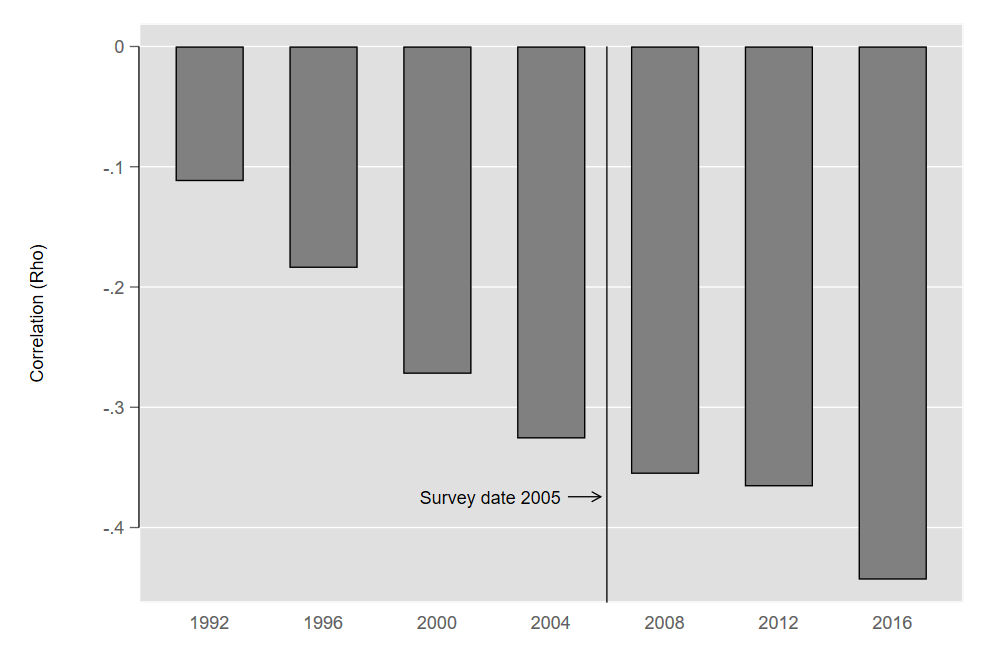

Nationally, housing remains one of the last remaining cross-cutting issues: there are pro- and anti-housing Republicans just as there are pro- and anti-housing Democrats. Red states tend to regulate housing development less (Figure 1), but the causation probably runs from lack of strict zoning to partisanship rather than the other way around (Figure 2). The details make a difference, though. I remember speaking to a Republican Minnesota state senator a few years ago, who drew a distinction between types of housing. “We want more single-family, and the other side wants more multifamily.” (To date, Minnesota has failed to pass any statewide housing deregulation.)

Note: Zoning stringency is measured by a survey of municipal land use officials. For presidential vote shares, higher values mean more Democratic support.

Some of the explanation for why northeastern Republicans oppose housing bills is that many of these housing bills have not been clearly deregulatory or have been nakedly partisan and left-wing, like the Connecticut bill, which strengthened rent regulation and enacted large giveaways to labor unions on top of its pro-housing measures. In other cases, good legislation like Massachusetts’ MBTA Communities Act has attracted Republican opposition (despite support from then-Governor Charlie Baker) because of its focus on zoning for multifamily housing, which is assumed to be mostly occupied by renters rather than condominium owners.

We should also question whether northeastern Republicans are always opposed to statewide pro-housing legislation. In Vermont, Republicans overwhelmingly supported 2023’s S 100 (now Act 47), relaxing the stringent requirements of the state’s environmental policy act, known as Act 250, and it passed into law easily. Last year, they opposed H 687 (now Act 181), which liberalized multifamily housing in infill locations while restricting suburban and rural development, but it passed over Gov. Phil Scott’s veto. In New Hampshire, Republican legislators are probably about 55 percent anti-housing and 45 percent pro-housing, depending on the bill, but every major center-right organization, including the free-market Josiah Bartlett Center, the socially conservative Cornerstone Action, the Business and Industry Association, Americans for Prosperity, and the New Hampshire Liberty Alliance, supports zoning reform.

What drives these differences in Republican views across states? The answer lies in a combination of factors.

- Beginning in the 1970s, a conservative property rights rebellion began in the western states. The “wise use” movement, as it came to be called, also took hold in Vermont, where I once spoke to a group called Citizens for Property Rights that originally formed to oppose Act 250. This movement was a reaction to environmentalist land-use regulation, and traces of that pro-property rights mentality survive to a greater extent among western Republicans than among northeastern ones. But western Republicans aren’t uniformly supportive of property rights, as we’ve seen in Colorado, where most (but not all) Republicans have voted against housing deregulation.

- As already mentioned, individual bills can be tilted for or against traditional Republican priorities. Unsurprisingly, in states where Democrats control the legislature, successful housing legislation tends to be tilted toward Democratic priorities (supporting unions, retaining or enhancing some environmental reviews, promoting multifamily over single-family, regulating rents, etc.).

- In metro areas with a history of political trauma related to urban riots, forced busing, and related issues, Republicans tend to be more protective of the suburbs and don’t mind a high-cost housing wall around cities that, to their minds, keeps urban problems at bay. The work of political scientists Jessica Trounstine, Eitan Hersh, and Clayton Nall strongly supports various elements of this conjecture.

The last one in particular seems to help explain why so many right-wing activists in New Hampshire oppose zoning reform. I have tried to have reasonable conversations with them about what underlies their objections, and once we clear away the rationalizations about “local control” and so on, I can sometimes get to what seems to be their authentic fear: that these bills will allow for high-rise apartment buildings that will import impoverished criminals.

That fear seems out of all proportion to what these bills would actually do. Their main target this year was Senate Bill 84, which essentially would have required towns to have some place where you’re allowed to build a house on two acres. Two acres! Far from solving the housing affordability problem, this bill would simply have curbed some of the grossest excesses of “expropriation-by-regulation” in New Hampshire towns. Still, because of the outcry, it was retained in committee in the House after easily passing the Senate.

My impression, admittedly anecdotal, is that most of the vociferous opponents of zoning reform in New Hampshire grew up near Boston or New York, and have internalized the view that zoning is some kind of symbolic totem with which to stave off the darkness. The details of legislation don’t matter; what matters is maintaining the status quo at all costs. By contrast, Republican farmers in rural northern New England have the same mentality as western ranchers and miners: hands off my property! In Vermont, remote, rural, and stagnant enough to lack a big suburban Republican constituency, and in New Hampshire, which has a uniquely large libertarian bloc in the Republican Party, Republican YIMBYism stands a chance that it might not, unfortunately, in the rest of the Northeast, with the possible exception of Pennsylvania.

If these conjectures are correct, getting Republicans to support pro-housing-supply reform in the Northeast and Midwest will require: 1) moderate bills that put as much emphasis on freeing up land for single-family development as they do on new rental housing, and 2) a focus on solutions like speeding up permitting, compensation for regulatory takings, and neighborhood-option upzoning that leave the symbolic core of zoning untouched.