In 1988, when Robert Lawson was a first-year economics graduate student at Florida State University, he was surprised one day to look up and see Dr. James D. Gwartney standing in front of him. He had come down from a different floor of the Bellamy Building to find Lawson. That was unusual, because grad students were normally summoned by tenured professors, not sought out by them.

But in this case, Gwartney had an assignment that was considerably more interesting than grading papers or returning a library book. He had received a letter inviting him into a group attempting to construct an index to measure economic freedom. Gwartney’s first reaction was that it was a “harebrained” idea. How could you quantify such a thing? Then he checked the letter’s sender: Milton Friedman.

Gwartney decided this might be a rabbit hole worth going down. He offered Lawson the chance to go with him.

The Economic Freedom of the World Index

In 1996, the Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) Index debuted. The model aggregated dozens of variables into a single figure for each nation, between 0 (the least economic freedom) and 10 (the most economic freedom). The report officially launching the index was co-authored by Gwartney, Lawson (who had finished his PhD in 1992), and Walter Block (then of Holy Cross). Friedman wrote the foreword.

Since that time, the EFW Index has offered researchers the only objective, mathematically transparent measure of economic freedom on a country-by-country basis (a competing index from The Heritage Foundation includes a subjective component). It incorporates variables from five areas (size of government, legal system and property rights, sound money, freedom to trade internationally, and regulation).

As of 2022, the index had been cited in over 1,300 peer-reviewed journal articles. An annual report now includes readings for 165 nations, with many going back to 1970. And the data are filled with stories.

Chile

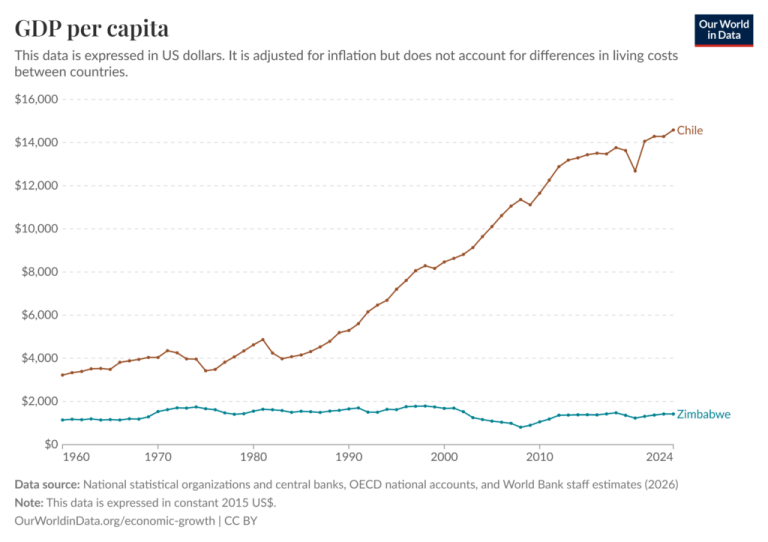

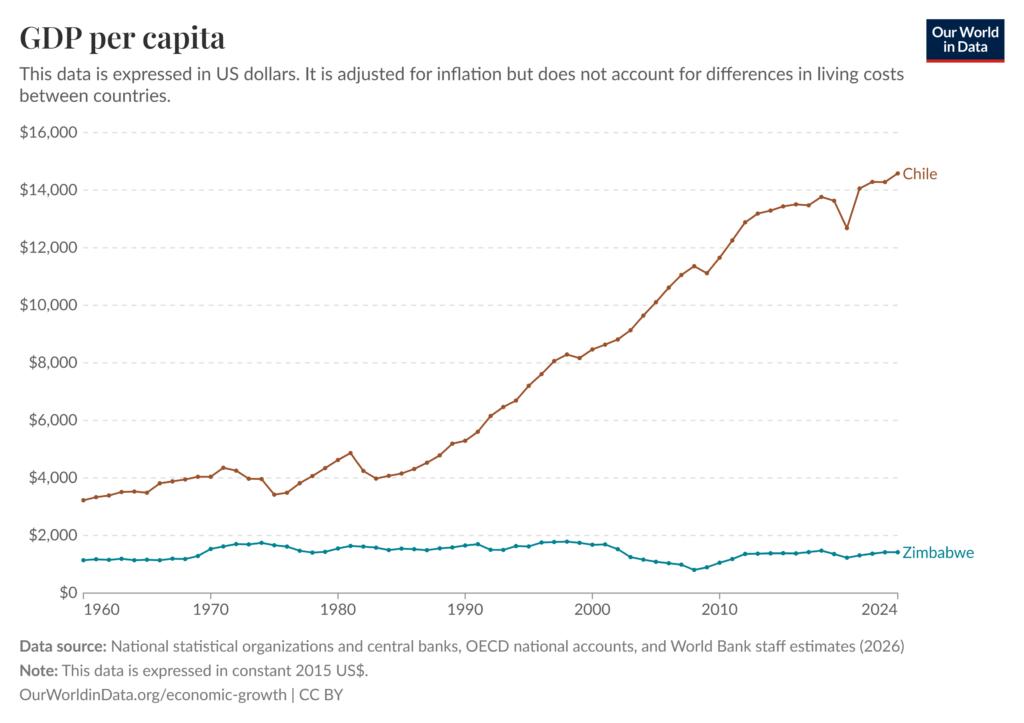

In 1970, for instance, Chile’s EFW Index was in the bottom quartile globally at 4.69. This was the year socialist Salvador Allende won the presidency with only 36 percent of the popular vote (no candidate having won a majority, the legislature chose him). A slew of socialist reforms followed. Banks were nationalized, price controls were instituted and money printed like there was no tomorrow. Predictably, private investment plummeted and inflation spiked as the nation plunged into a recession.

A military coup overthrew Allende in 1973, with an alleged but uncertain level of help from the Nixon Administration and in particular Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. The new Chilean leader, Augusto Pinochet, was no socialist. But he did wield power like one—through brutal repression. And while his advisors included free-market economists such as Hernán Büchi, the regime’s policies were at best a burlesque of economic freedom.

Consequently, in 1975 Chile’s EFW Index reached an all-time low of 3.82. But after Pinochet was defeated in a 1988 plebiscite, the nation began to liberalize its society and its economy. In 1990, it moved into the top quartile of EFW rankings for the first time, with a reading of 6.89. While the nation’s economic and political path since has not always been smooth, Chile has stayed in the top quartile every year. What does such economic freedom mean on the ground?

According to the current CIA World Factbook, since the 1980s Chile’s poverty rate has fallen by more than half.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is another story. It began 1970 in a slightly better position than Chile, with an EFW reading of 4.96. It was known as Rhodesia then, a new republic trying to transition from British rule. The decade of the 1970s was one of political instability as a government led by Prime Minister Ian Smith contended with both Marxist and Maoist communist groups for the country’s future. The Maoist Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) prevailed, changing the nation’s name to Zimbabwe in 1980. ZANU has been in control of Zimbabwe ever since, with Robert Mugabe serving as prime minister or president from 1980-2017.

While ZANU has not remained strictly loyal to the Maoist model of communism, and has attempted some pro-business policies, government intrusion in the economy remains high. Property rights are not well enforced. Corruption is systemic and regulations stifle both new business formation and foreign investment. Consequently, since 2000 Zimbabwe has remained in the bottom quartile of EFW Index scores, with a 2023 reading of 3.91, a 21 percent decline from 1970.

These numbers have tragic implications, especially for the least privileged. In 2023, Zimbabwe’s poverty rate was over 70 percent and an estimated half the population lived on less than $1.90 per day.

Apart from humanitarian concern, should we worry about these things in the US? Economic freedom here is too deep to ever uproot, right?

If the EFW Index teaches us anything, it’s that economic freedom, like freedom in general, is inherently fragile. No one understands that better than Lawson.

Today he directs the Bridwell Institute for Economic Freedom at Southern Methodist University and continues to manage the EFW Index as a senior fellow of the Fraser Institute in Canada, which sponsors the index. In 2024, he wrote a remembrance of James Gwartney in The Daily Economy.

After decades of involvement with the EFW Index, Lawson remains optimistic about the prospects of global economic freedom, but guardedly so.

“The general trend is still toward freedom,” he says, “but since 2000 it’s less steep.”

If history is any guide, increasing the slope would have an amazing impact on human flourishing worldwide. If national leaders worried about their EFW Index the way college football teams do their playoff rankings, we might see more stories like Chile, including in places like Zimbabwe.